Diemer.ca

Radical Digressions

Articles Lists

- Selected Articles

- Articles in English

- Articles in French

- Articles in Spanish

- Articles in German

- Articles in Other Languages

- Articles A-Z

- RSS feed

- Subject Index

Selected Topics

- Alternative Media

- Anarchism

- Bullshit

- Capital Punishment

- Censorship

- Chess

- Civil Liberties

- Collective Memory

- Community Organizing

- Consensus Decision-making

- Democratization

- Double Standards

- Drinking Water

- Free Speech

- Guilt

- Health Care

- History

- Identity Politics

- Interviews & Conversations

- Israel/Palestine

- Libertarian Socialism

- Marxism

- Men’s Issues

- Moments

- Monogamy

- Neo-Liberalism

- New Democratic Party (NDP)

- Political Humour/Satire

- Public Safety

- Safe Spaces

- Self-Determination

- Socialism

- Spam

- Revolution

- Trotskyism

Blogs & Notes

- Latest Post

- Notebook 11

- Notebook 10

- Notebook 9

- Notebook 8

- Notebook 7

- Notebook 6

- Notebook 5

- Notebook 4

- Notebook 3

- Notebook 2

- Notebook 1

Compilations & Resources

- Connexions

- Other Voices newsletter

- Seeds of Fire

- Alternative Media List

- Manifestos & Visions

- Marxism page

- Socialism page

- Organizing Resources

- People’s History, Memory, Archives

- Connexions Quotations page

- Sources

- What I’ve been reading

- What I’ve been watching

Words of Wisdom

- The emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves.

- – Karl Marx

Favourite Links

How they shot those campus bums

Review by Ulli Diemer

The Truth About Kent State: A Challenge to the American Conscience

by Peter Davies

and The Board of Church and Society of The United Methodist Church,

Farrar, Straus, Giroux; $11.50 - $3.85.

On March 5, 1770, British troops fired - in self-defense, they claimed - into a rioting mob in the city of Boston. Immediately afterwards, the soldiers responsible were arrested and indicted by the British government; several were convicted of manslaughter. Nevertheless, the incident so outraged public opinion in America that the Boston Massacre, as it became known, proved an important contributing factor in the anger that led to the outbreak of the American Revolution.

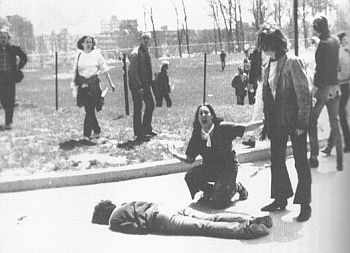

Some two hundred years later, on May 4, 1970, troops of the Ohio National Guard fired into a group of demonstrating students - allegedly in self-defense - killing four, and wounding nine others, several seriously.

"One modest suggestion for my friends in the academic community: the next time a mob of students, waving their non-negotiable demands, starts pitching bricks and rocks at the Student Union - just imagine they are wearing brown shirts or white sheets and act accordingly."

— Spiro Agnew, April 1970

Although student fury at the event developed into demonstrations and strikes across the country, the response of the general American public differed markedly from that on the campuses, or from that of 1770. More than 60 per cent of the population condoned the shootings. More telling - and ominous - yet was the fact, revealed in interviews with some 400 Kent State students after the shootings, that they "had been told by their parents that it might have been a good thing if they had been shot."

This background, this willingness to condone the use of force against students whatever the occasion, may help to explain the lack of any action whatever against the killers by the government or the courts.

The killings were, it is almost certain, a case of premeditated murder, a conspiracy on the part of a number of guardsmen to "get those bastards", the campus long hairs. Other military and civilian officials, while not complicit, participated in a cover-up. It was more important to them to protect their system of authority, and its reputation, than to have the truth discovered, and acted on.

The facts of the case, as exhaustively presented in The Truth About Kent State, are damning enough. Even more damning, then, is the fact that, to date, three-and-one-half years later, nothing has been done about them.

The major conclusions reached by the FBI and the U.S. Department of Justice are the following:

· The shooting was not necessary and was not in order.

· There were no snipers; the guardsmen were never fired on.

· The guardsmen ware not surrounded; their path was clear

and unobstructed.

· The Guard still had tear gas available when the gunfire

took place.

· At the time of the shooting, no student posed a threat

to the lives of the guardsmen.

· In addition, the Department of Justice stated that it had

reason to believe that, subsequent to the shooting, guardsmen had

conspired to fabricate their story of sell-defence. Of those guardsman

who had not admitted shooting, at least two were lying.

Despite these conclusions, Attorney General John Mitchell closed the case, "satisfied that the Department (of Justice) has taken every possible action to serve justice".

So ended - at least in the courts - a story that began on April 30 when President Nixon ordered American troops to invade Cambodia.

In the first days of May, demonstrations broke out in protest across the country, including Kent State University in Ohio. On May 2, during the evening, the empty campus ROTC building was set on fire and burned to the ground. In the aftermath, National Guard troops were sent onto the campus although the campus authorities had not requested them, believing there was nothing in the situation that would require their presence. The use of the troops may well have been due to the determination of Ohio Governor Rhodes, on the eve of a crucial election primary, to appear as a strong law-and-order man.

"(Student radicals are) the worst type of people that we harbor in America... We are going to eradicate the problem, we're not going to treat the symptoms."

— Governor James Rhodes of Ohio, May 3, 1970

Nevertheless, the Guard made itself busy on campus by breaking up rallies against the war. A number of students were bayoneted, with the result that many previously apathetic students became hostile to the Guard.

On May 4, a rally had been called for noon. University President White was unconcerned; he went into the town for lunch.

In his absence, National Guard General Canterbury decided to disperse the peaceful assembly. "Only when the Guard attempted to disperse the rally", reported President Nixon's Commission on Campus Unrest, "did some students react violently."

"These students are going to have to find out what law and order is all about."

— Brigadier General Robert Canterbury, commander of the troops at Kent State, minutes before the shooting

The violence took the form of sporadic rock-throwing by a few people. Only one guardsman was hurt seriously enough to require any kind of medical attention; and this individual, a Sgt. Shafer, was well enough 15 minutes after his injury was sustained, according to the FBI report, to deliberately aim at and shoot down student Joseph Lewis, standing 70 feet from the Guard, who had taunted the guardsmen with an upraised finger. For this, Lewis was maimed for life. For the guardsmen, the 'violence' was considerably less than that which the same riot-trained troop had encountered earlier in the week during a strike. At that time, they had endured serious injuries and sniper fire without firing in return.

"Flowers are better than bullets."

— Allison Krause to a National Guard officer the day before she was shot down.

The Guard cleared the campus common of demonstrators, marched to a football field adjoining a parking lot, and turned to retrace its path. Some harassment of the Guard was taking place at this time. It was not severe enough, however, to prevent a single uniformed officer from walking through the midst of the thickest part of the crowd.

Immediately before their return march, a number of guardsmen were observed going into a huddle on the practice field. Then, as the Guard reached the crest of a small hill on their return march, a number of them whirled simultaneously and began to fire - without any warning whatever - into the parking lot below. The Guard later claimed that no order to fire had been given, that a number of men (at least 28) fired independently in self-defense. Up to the point of the gunfire, however, most of the men involved had had their backs to the students, and the distance between them and the students had been increasing constantly. No one was moving to attack the Guard; its path was clear.

When the shooting began, students began to run or take cover. Nevertheless, the Guard continued firing for 13 seconds. One of those killed, William Schroeder, was shot in the back while lying on the ground, trying to take cover. The closest victim was 70 feet from the Guard, only one of the others was within 200 feet. Eight of the 13 were 300 feet or more away. None, of course, were armed.

Numerous photographs exist of the shooting and the moments prior to it, from all angles. They, and much other evidence, made it easy for the US Department of Justice to conclude that the claims of the guardsmen to have acted in self-defense were "fabricated".

The immediate claim that there had been a sniper on a building was conclusively disproven; at any rate, even had there been one; this would have in no way justified shooting into the parking lot. A government investigation concluded that at least some of the guardsmen were lying in their stories. Considerable evidence was produced to support the contention that some guardsmen had planned the shooting among themselves. Despite this, the Nixon administration refused to act. The reason given was that it would be unlikely that prosecution of individual guardsmen would be successful, rather unconvincing given its claim to know that some had lied to investigators (itself a crime) and more unconvincing when put in the light of its extreme quickness to prosecute other, more questionable, conspiracy cases: the Chicago Seven, the Berrigans, Daniel Ellsberg.

"With so many unanswered questions surrounding the four murders at Kent State to burden the American conscience, I find it almost incomprehensible that the U.S. Attorney General could close the official books on the May 4th tragedy while paradoxically agreeing with previous investigations that the shooting deaths were ‘Unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable’".

— An Ohio National Guardsman present at Kent State

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the government decision had something to do with the unpopularity of students, and the view. held by many, that the students 'got what they had coming'.

The Truth About Kent State is an attempt to overcome that attitude with what was once considered a powerful weapon: the truth. The case argued sketchily in this review is put exhaustively and painstakingly, bolstered by a wealth of facts, testimony, and over 70 photographs. It stands as an indictment. Whether it can become what it subtitle claims for it, A Challenge to the American Conscience, remains to be seen.

Published in The Varsity, Friday December 7, 1973

Subject Headings

Murder -

Military/Violence Against Civilians