Ulli Diemer — Radical Digressions

Notebook #9

- CreativeDisruption

- A new laneway mural by Nick Sweetman

- What Next?

- Fallacies about free public transit

- Faith, Hope and Persistence

- A Theological Moment

- Toronto’s newest street sign

- Taking a Stand

- Morality in an Amoral World

- Don’t Use Bleach

- We Don’t Repeat

- Thinking Clearly in a Time of Crisis

- M is for Miriam (book announcement)

- Strange Sounds Up in the Trees

- Some musings about risk

- Eratosthenes: Measuring the Earth on the Solstice

- Longing for freedom, and grieving loss: Reflections on watching swifts on a summer evening

- Social Distancing

- An Evening Paddle

- Heat Wave

- Butterfly

- November 11

- Nature Calendar 2021

- Adding up to Zero

- The people who are preparing for war, and the lies they tell

- Beyond the Walls

- Notwithstanding Clause

- Deadly Overcrowding

- Situation Normal – April 1, 2021

- How I got vaccinated

- The intelligence of ravens and the foolishness of (some) humans

- White-throated Sparrow

- Deadlines

- Situation Normal – May 1, 2021

- Situation Normal – June 1, 2021

- Afghanistan and the ‘experts’

- Watching the News

- The bright side

- Covered Bridge Potato Chips

- Red tape bad, more red tape better

- Anti-Vaxxer Protest

- Things are getting better and better and bettxrxr and bxzyxxx

- Notebook 8

Articles Lists

- Selected Articles

- Articles A-Z

- Articles in English

- Articles in French

- Articles in Spanish

- Articles in German

- Articles in Other Languages

- RSS feed

- Subject Index

Selected Topics

- Alternative Media

- Anarchism

- Bullshit

- Capital Punishment

- Censorship

- Chess

- Civil Liberties

- Collective Memory

- Community Organizing

- Consensus Decision-making

- Democratization

- Double Standards

- Drinking Water

- Free Speech

- Guilt

- Health Care

- History

- Identity Politics

- Interviews & Conversations

- Israel/Palestine

- Libertarian Socialism

- Marxism

- Men’s Issues

- Moments

- Monogamy

- Neo-Liberalism

- New Democratic Party (NDP)

- Political Humour/Satire

- Public Safety

- Safe Spaces

- Self-Determination

- Socialism

- Spam

- Revolution

- Trotskyism

Snippets

Hope is about possibility, not certainty. Even when we know that we are rowing against the tide, as we often are, we know that the future is not preordained. We know the future is shaped by human actions, and so we act. And we hope that our actions will help to steer the future in the direction we want to go in.

Faith, Hope and Persistence

From its beginnings, one of capitalism’s prime imperatives has been an all-out and never-ceasing assault on the Commons in all its manifestations. Common land, common water, public ownership – anything rooted in the ancient human traditions of sharing and cooperation is anathema to an economic system that seeks to turn everything that exists into private property that can be exploited for profit.

The Commons

One of the things that the existence of the Golden Rule tells us is that we humans are imperfect and full of contradictions. Even when we know what we should do, we sometimes fall short, and need to be reminded or held to account. That, no doubt, is why discussions of the Golden Rule so frequently stress compassion, forgiveness, and second chances. It recognizes that there are times when we need to forgive, and times when we need to be forgiven.

Morality in an Amoral World

Blogs & Notes

- Latest Post

- Notebook 11

- Notebook 10

- Notebook 9

- Notebook 8

- Notebook 7

- Notebook 6

- Notebook 5

- Notebook 4

- Notebook 3

- Notebook 2

- Notebook 1

- Moments

- Scrapbook

Compilations & Resources

- Connexions

- Other Voices newsletter

- Seeds of Fire

- Alternative Media List

- Manifestos & Visions

- Marxism page

- Socialism page

- Organizing Resources

- People’s History, Memory, Archives

- Connexions Quotations page

- Sources

- What I’ve been reading

- What I’ve been watching

- Miriam Garfinkle

- Moments with Miriam

Favourite Links

- Break Their Haughty Power

- Bureau of Public Secrets

- Canadian Dimension

- Climate & Capitalism

- Connexions

- CounterPunch

- The Ecologist

- Green Left Weekly

- Independent Science News

- Insurgent Notes

- The Intercept

- Jacobin

- Johnathan Cook

- Libcom

- Marxist Archive

- Medialens

- Noam Chomsky

- Solidarity

- Sources

- More Links...

Words of Wisdom

- Never do anything against conscience even if the state demands it.

- – Albert Einstein

- Whoever is winning at the moment will always seem to be invincible.

- – George Orwell

- The best way to destroy an enemy is to make him a friend.

- – Abraham Lincoln

Snippets

It is one of the essential attributes of power that it insists on secrecy. Or, more precisely, those who wield power over others routinely claim that the details of what they do, and why they do it, are far too sensitive to be revealed to the public.

Secrecy and power

Radical Digressions

Ulli Diemer’s Notebook #9

Nature Calendar September: Monarch

September 1, 2019 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, September: Monarch butterfly, Toronto Islands. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Time for creative disruption?

September 2, 2019 - #

The business world, including business schools and the corporate media, is in love with “disruptive innovations” which "disrupt" established ways of doing things. Like all buzzwords, “disruption” has become a woolly cliche whose meaning is rarely defined. But we are meant to understand that “disruptive innovations” are great, the very epitome of progress – and anyway, they’re inevitable, so there is no use questioning them or trying to stop them.

But what gets to be called a “disruptive innovation?” We tend to think that it involves a new technology of some kind, but in fact that is rarely the case. The disruptive innovations we are seeing typically involve a new way of doing something that is already being done, using already-existing technologies.

So what about them is new?

Not so much, actually. They are simply the latest incarnation of a process as old as capitalism itself. Karl Marx described it more than 150 years ago. It boils down to this:

1) Wherever possible, eliminate jobs, because paying workers is expensive. Fewer workers = higher profits.

2) Where it is necessary to have workers, reduce their wages to the absolute minimum and make their working conditions as precarious as possible, to undermine their ability to organize and fight for higher wages and better working conditions.

3) Keep telling people that what is being done to them is (a) progress and (b) inevitable.

Could things be different?

It is possible to imagine other kinds of “disruptive innovations,” different ways of doing things which would disrupt the status quo. To bring them about, we would need to come up with creative ideas, persuade other people that they are good ideas, and organize to bring them about. Here are a few ideas, none of them all that original, which would qualify as creative disruptions of the status quo.

1) Free public transit. Eliminate fares and improve service. This would, at the same time, fight climate change, help the working poor, and save all the money wasted on fare collection. We urgently need to transition away from our dependence on automobiles. Transit service that is reliable, efficient, safe, and free is absolutely necessary if we are to accomplish that transition. Let’s disrupt the hegemony of the automobile by making transit cheaper and better.

2) Provide good housing for everyone who needs it. Our current system, which treats land and housing as commodities and relies on private developers to build housing, has failed miserably to provide good affordable housing. Let’s disrupt the real estate industry, stop treating land and housing as commodities, and start building homes for people, not profit.

3) Disrupt the military-industrial complex. Far from making us safe, the madness of militarism threatens to trigger a war that would wipe out most of the human race. The military, and especially the U.S. military, which dwarfs all other countries, is also the single biggest producer of greenhouse gases and therefore a major cause of the climate crisis. And military production distorts the economy, producing for destruction while human needs remain unmet. A first step in disrupting the military-industrial complex would be to shut down all U.S. military bases in other countries. That’s not enough, but it would be a start on the road to the ultimate goal of eliminating the military entirely.

4) Disrupt the tax system. The rich keep getting richer, and the majority of the population keeps getting poorer. One obvious step is to radically change the tax system. Eliminate exemptions and preferential tax treatment for capital gains and investments. Make the tax system truly progressive. Set a maximum income for individuals (let’s be generous, and say $300,000 per year). Any income above that would be taxed at 100%. Tax wealth as well as income to prevent rich people from accumulating and holding on to obscene amounts of wealth.

Ulli Diemer

A new laneway mural by Nick Sweetman

September 27, 2019 - #

A new mural, by Nick Sweetman, has just appeared in the laneway which the City is about to designate as Miriam Garfinkle Lane.

Nature Calendar October: White-tailed deer, Manitoulin Island

October 1, 2019 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, October: White-tailed deer, Manitoulin Island. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

What Next? Other Voices – October 27, 2019

October 27, 2019 - #

Millions of us, in many different countries, came out in late September to demand action on the climate crisis. Around the world, in diverse ways, we are working to keep up the pressure. Time is short, and the tasks are huge.

In the midst of our activism and organizing, we need to keep asking ourselves some important questions: What are our goals? And what should we do to reach our goals?

The high of massive demonstrations is often followed by a slump of discouragement, when we realize that nothing fundamental seems to have changed as a result of our protests.

It may be worth remembering the history of other mass protests. In early 2003, a huge anti-war movement arose in reaction to the planned American invasion of Iraq. Some 36 million people came out in cities around to world to protest against the threat of this illegal war, launched on the basis of transparently false pretexts. Despite the massive protests, the war started, hundreds of thousands of Iraqis died, and the fallout continues to this day. The anti-war movement continued for some time longer, and then virtually disappeared, even though the threat of war has been increasing year by year, with the United States started pulling out of international arms control treaties and engaging in dangerous military provocations on the borders of Russia, China, and Iran.

The hard truth is that while mass protests can be energizing while they happen, their momentum can be difficult to sustain unless we are able to convert them into ongoing organizing.

To keep moving forward, we have to find ways of working together to create a counter-power to challenge capitalist system, including the political structures and institutions that sustain it. To put it another way, we have to understand where the real power lies, and we have to have strategies for challenging that power with the power of vast numbers of people, organizing together. We also have to have a clear idea of what our goals are – not only specific goals related to carbon in the atmosphere, but goals of worldwide system change.

This issue of Other Voices includes a number of articles, books, and other resources which suggest approaches to, and answers to, some of those questions.

Ulli Diemer

See the October 27 issue of Other Voices here.

Keywords: Anti-Capitalism – Capitalist Crises – Climate Change – Climate Justice – Ecosocialism – Just Transition – Movement Building – Working Class & Climate Change –

Nature Calendar November: Scarborough Bluffs

November 1, 2019 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, November: Scarborough Bluffs. The light-coloured bumps in the water are Trumpeter Swans. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Fallacies about free public transit

November 25, 2019 - #

Whenever the movement for free public transit shows signs of gaining public support, the media digs up ‘experts’ who furrow their brows and tell us what an impractical idea it is. An article in the November 25 Toronto Star is a case in point. Here is a letter I wrote in response:

Opponents of free public transit resort to two fallacious arguments.

The first is that good transit is more important than free transit in persuading commuters to take transit. This is not an either-or choice. It is quite possible – and necessary, if we are to avert climate catastrophe – to have transit that is good, accessible, safe, and free.

The second fallacy is the claim that providing free transit will be expensive. This is false. The operating costs of a transit system are the same whether the costs are paid out of fares, or out of taxes, or some combination. Providing free transit would in fact eliminate the substantial costs of collecting and enforcing payment, including the horrendous costs of the ongoing Presto debacle.

Free transit simply means that transit is paid for out of general tax revenues, rather than fares. Free transit benefits everyone, including those who don’t use it. It is an idea whose time has come.

Ulli Diemer

Keywords: Municipal Transit – Public Transit – Public Transportation – Urban Transportation

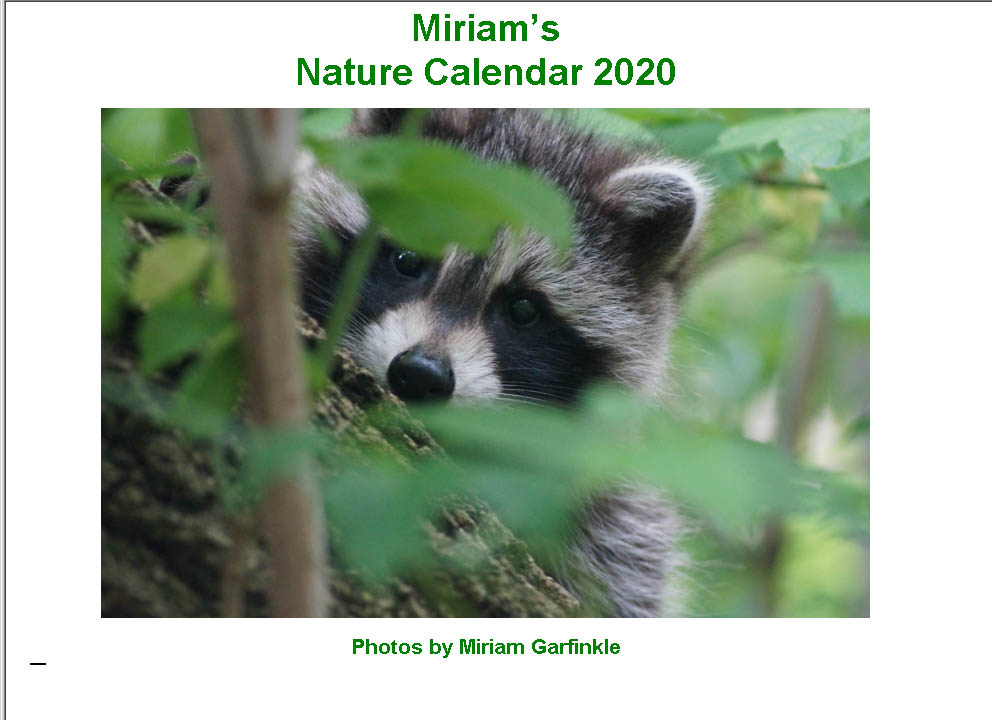

Miriam’s Nature Calendar 2020

November 26, 2019 - #

Again this year, I created a calendar featuring photos taken by my partner, Miriam Garfinkle, who died on September 15, 2018. Miriam was frequently out in nature, and she’d often have a camera with her. As I did last year, I gathered up some of the photos she took and compiled them in Miriam’s Nature Calendar 2020. I printed about 130 copies for friends and family. The PDF version is available online.

Nature Calendar December: After the ice storm

December 1, 2019 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, December: After the ice storm, Toronto, December 2013. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Faith, Hope and Persistence Other Voices – December 15, 2019

December 15, 2019 - #

When we look at what is happening in our world, it can be difficult to believe that there are grounds for hope, let alone faith. And yet we – we humans – continue to live and act in ways that testify to our hopes, and to our faith in the possibility of a better future. We plant gardens and trees, we have children, and we resist injustice and act to protect the planet we share.

Hope is something quite different from optimism. Optimism – and pessimism – assess the likelihood of something happening. But being optimistic or pessimistic is irrelevant to standing up for justice and defending the earth. For most of us at least, our moral principles aren’t based on a calculation of the odds. And in fact most acts of resistance, and most movements for justice, arise in the face of what are often overwhelming odds. They are the powerless challenging those with entrenched power. It is only by acting that people who feel powerless come to feel that they do have power. And when we act, that which seemed impossible to achieve starts to become possible, because enough people believe it is possible and are working together to make it so.

Hope is about possibility, not certainty. Even when we know that we are rowing against the tide, as we often are, we know that the future is not preordained. We know the future is shaped by human actions, and so we act. And we hope that our actions will help to steer the future in the direction we want to go in.

When we act collectively, we are also expressing our faith in other people, and in ourselves. Not blind faith – we know our own contradictions and faults, and we know all too well the immorality and cruelty that humans, or at least some humans, are capable of. But we also know, from our own life experience, that part of the common heritage of humanity are impulses to create community, to share, to love one another, to treat others as we ourselves would wish to be treated. And the fact that these capacities exist is a basis for faith in people, including ourselves, and in our ability to change and to rise to our potential to be who we are capable of being. By working to change the world, we change ourselves.

Nature Calendar January: Black-capped Chickadee

January 1, 2020 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, January: Black-capped Chickadee, Toronto. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

A theological moment

January 3, 2020 - #

I’m walking to work along Bloor Street this morning. Two guys are smoking in a doorway. One of them stops me: “Excuse me. My friend and I, we are having a discussion. Do you know, what is purgatory?”

I reply: “Yes, it’s where you go when you aren’t good enough to go straight to heaven, but not bad enough to go to hell. It is an in-between place, sort of like jail, where you stay for a period of time, and then when you have served your time, you go to heaven.”

Guy: “So you do go to heaven after?” He looks meaningfully at his friend.

“Yes,” I reply. “If you believe in that kind of thing.”

They seem happy with my answer. I go on my way.

Toronto’s newest street sign

January 4, 2020 - #

Toronto’s newest street sign went up yesterday on Miriam Garfinkle Lane. I don’t think I ever had a favourite street sign before, but this one is now definitely my favourite.

Nature Calendar February: Winter Ducks, Leslie Street Spit

Febuary 1, 2020 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, February: Winter Ducks, Leslie Street Spit. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Taking a Stand Other Voices – February 18, 2020

February 20, 2020 - #

Psychologists call it cognitive dissonance. George Orwell called it double-think. Some of us might call it organized hypocrisy.

Call it what you will, it surrounds us. The government proclaims its commitment to ‘reconciliation’ with indigenous people, and says that its relationship with them is its most important relationship. At the same time the RCMP, following an order by a colonial court, invades unceded indigenous land and arrests people for occupying their own land. Governments mouth platitudes about the importance they place on dealing with the climate emergency while at the same time they build new pipelines and approve massive new tarsands projects. The biggest polluter on the planet – the U.S. military – meanwhile receives constant increases in its budget, even while it pursues demented schemes to take us to the edge of war, mostly recently by deploying a new generation of “low-yield” thermonuclear weapons on submarines. The theory, presumably, is that if the U.S. drops a few “low-yield” nuclear bombs on Russia or China, the Russian and Chinese won’t mind too much, and won’t retaliate.

All this is business as usual. Fortunately many people across the country, and around the world, are saying no to business as usual. They are taking a stand and disrupting business as usual.

In this issue of Other Voices, we spotlight the actions of people who are taking a stand and, in many different ways, are insisting on change.

Ulli Diemer

See the February 18, 2020 issue of Other Voices here.

Keywords: Indigenous Struggles – Militarism – Nuclear Weapons – Oil & Gas/Environmental Issues – Police Raids – Anti-Psychiatry – Direct action – Non-violence – Rural Women

Nature Calendar March: Red-breasted Merganser

March 1, 2020 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, March: Red-breasted Merganser, Toronto Island. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Morality in an Amoral World

March 19, 2020 - #

A crisis is a mirror.

It shows us – if we have the courage to see – who we are as individuals and as a society. The self-congratulatory poses of governments, politicians, and state institutions are confronted with the harsh test of reality. Each of us – as individuals, friends, families, neighbours, communities – face new and sometimes difficult challenges.

The novel coronavirus COVID-19 is such a crisis. Governments? Some are well-prepared, with solid public health systems and free health care for all. Meanwhile, in the US, in mid-February, two weeks after the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency of international concern, the Trump administration pushed ahead with major funding cuts to U.S. public health programs, including a $25 million cut to Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, and $85 million in cuts to the Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases program. In Ontario, when COVID-19 struck, public health authorities were facing the looming 27% cut to public health spending announced by the Ford government in its budget. (Belatedly, Ontario has just declared a state of emergency and put those cuts on hold – for now.)

In the confusing rush of events that mark a crisis, it is easy to be so focused on what is happening that we forget to ask why. Yet it is when we ask why that we confront the ethical and moral questions that illuminate who we are and what kind of society we live in.

Why, for example, are pharmaceutical companies competing to produce a vaccine for COVID-19? Why, instead of keeping their work secret, aren’t scientists around the world collaborating, sharing their research, and making the results freely available? Why isn’t this question even being asked in public discourse? It seems that we are supposed to take it for granted that, above everything else, the goal of scientific work should be to make a profit. U.S. government officials have already stated that an eventual COVID-19 vaccine may not be available to everyone in the U.S., let alone in poorer countries, because it may be ‘too expensive.’

We’ve moved backwards.

The worst epidemics in Canada and the U.S. in the last 100 years were the recurrent polio epidemics. In Canada, an estimated 11,000 people were left paralyzed by polio just between 1949 and 1954. In 1954 alone, there were 9,000 cases including nearly 500 deaths. In the U.S., in 1952, there were 58,000 cases of polio, resulting in 3,135 deaths and 21,269 cases of paralysis. The polio nightmare started coming to an end when Jonas Salk developed the first successful polio vaccine in 1955. The patent? None. Salk refused to patent his discovery: he wanted it to be freely available to everyone.

Salk himself was following in the footsteps of Fredrick Banting, Charles Best, and James Colip, the discovers of insulin. They did patent their discovery – and then sold the patent to the University of Toronto, for $1. They said they didn’t want to profit from a discovery for the common good.

Salk’s and Banting’s attitude would be unthinkable now. What capitalism has succeeded in doing, it seems, is to make it acceptable for corporations to engage in behaviour, on a large scale, which most of us, as individuals, would refrain from as a matter of common decency.

And indeed, as individuals, as friends, as a community, people continue to support and help each other in times of trouble. Informal networks of mutual support spring up, as they nearly always do in a crisis. Beyond the headlines about COVID-19 emergency measures, closures, and social distancing, there are countless stories about people reaching out and helping those who need help.

Yet capitalism tells us, endlessly, that selfishness is good and inevitable. In the place of morality, it proclaims an amoral vision in which nothing matters except making as much money as possible. Greed is good. Exploiting others, destroying the planet, condemning people to a life of poverty and suffering, it’s all good, as long as money can be made. Capitalism allows no moral qualms.

While there are some – too many, it’s true – who have internalized this attitude, most of us do not act this way in our own lives. Society could not exist if we did, because we need each other. As social beings, we survive and thrive to the extent that we can form and count on relationships that are built on mutual support, co-operation, and trust.

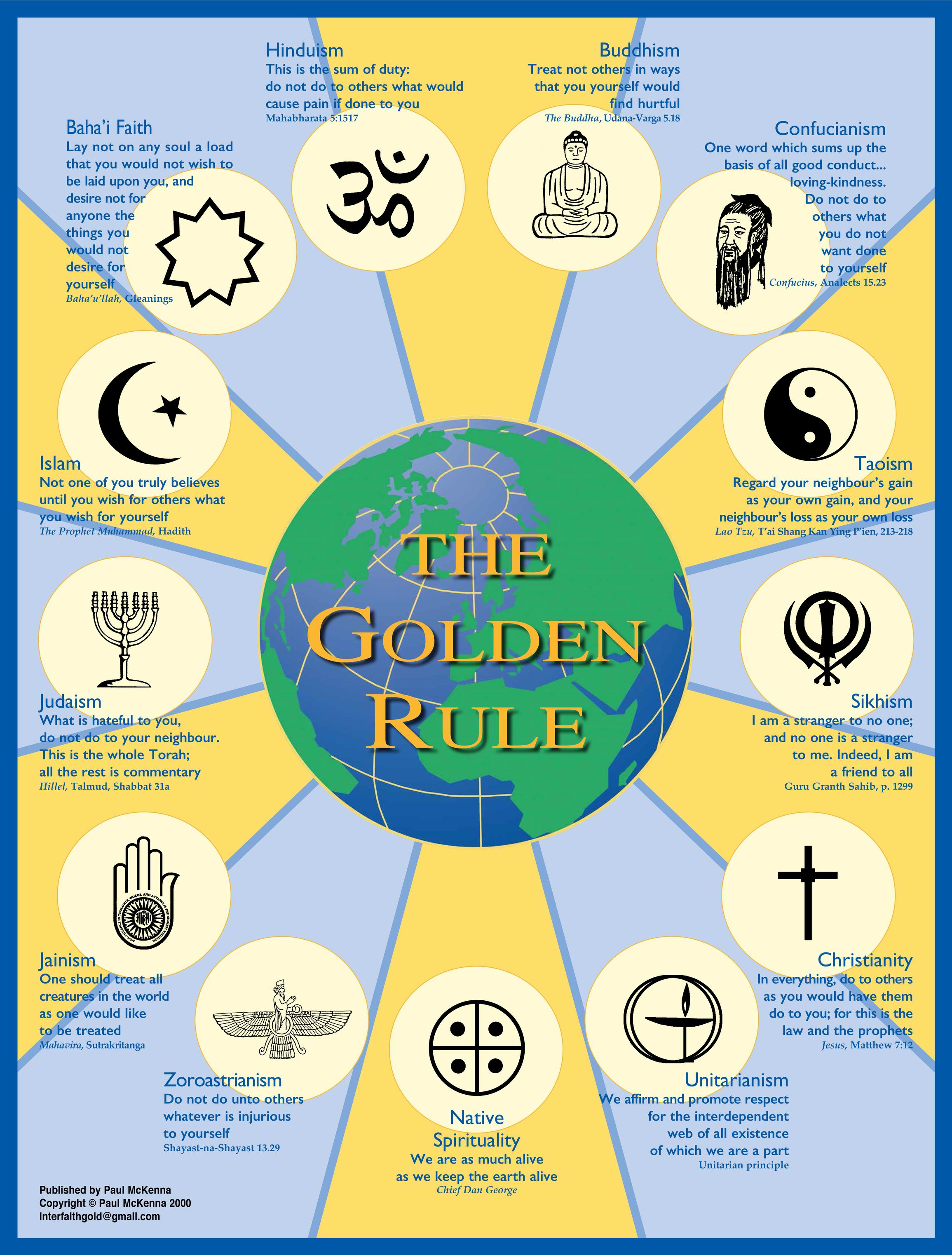

The moral principle that has come to be known as the Golden Rule embodies this truth. Versions of what we call the Golden Rule emerged in many different religions, as the Golden Rule poster below illustrates. The fact that it is part of so many different traditions tells us that it pre-dates those traditions: it is embedded in human nature itself.

If we, or at least most of us, did not recognize the fact that each of us is worthy of respect and deserving of having our needs met, we could not survive as a social species. At the same time, if treating others as we ourselves would wish to be treated were always perfectly natural and automatic, then we wouldn’t need a Golden Rule. We don’t have a rule that tells us to breathe. We just do it.

One of the things that the existence of the Golden Rule tells us, then, is that we humans are imperfect and full of contradictions. Even when we know what we should do, we sometimes fall short, and need to be reminded or held to account. That, no doubt, is why discussions of the Golden Rule so frequently stress compassion, forgiveness, and second chances. It recognizes that there are times when we need to forgive, and times when we need to be forgiven.

At the same time, no rule, no matter how profound, is a substitute for thinking critically about real-life situations. For example, few of us would advise a woman in an abusive relationship to return to her violent partner and give him a second – third – fourth – fifth chance. There are times when anger is a healthier response than turning the other cheek.

There are occasions, in fact, when, confronted with the life’s complexities, we might also want to keep in mind George Bernard Shaw’s contrarian dictum: “The golden rule is that there are no golden rules.”

Nor does the Golden Rule, by itself, guide us in dealing with those who have power over us, especially when that power is wielded to oppress. To deal with them, we need to draw on another part of our human nature: our impulse to come together and support each other to fight for justice. As Cornell West has said, “Justice is what love looks like in public.”

The coronavirus outbreak is a crisis that challenges us to look beyond our own immediate concerns and ask ourselves what kind of world we want to live in. We don’t have much time: climate change will make this virus seem like a picnic.

But we do have some time right now, because many of us have had our lives put on hold. Let’s try to use that time as constructively as we can.

There are things we can do to help, like donating money, even while we are self-isolating. There are people who are facing this virus – and other concurrent public health disasters, like malaria, which kills 3,000 children every day – under infinitely worse conditions than we are. Think of Yemen, Gaza, Congo. Venezuela and Iran are trying to cope with their outbreaks even while the United States is tightening sanctions on medical and humanitarian supplies.

They need our active solidarity.

One step you can take today is to donate to Tarek Loubani’s GLIA Project, which is printing 3D masks and stethoscopes for Palestine and other under-served communities whose capacities for dealing with a health crisis are much worse than ours. You can donate to them here here.

Please help. And stay well!

Ulli Diemer

This article appeared in the March 19, 2020 issue of Other Voices.

Related Reading:

Abandoning The Public Interest

Contamination: The Poisonous Legacy

of Ontario’s Environmental Cutbacks

Public Safety: Other Voices, June 26, 2017

Nature Calendar April: Leopard Frogs

April 1, 2020 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, April: Leopard Frogs, MacGregor Point, May 2018. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Don’t Use Bleach

April 16, 2020 - #

Among the many myths about the COVID-19 coronavirus is the theory that you can use bleach on yourself to kill it. DO NOT do this!

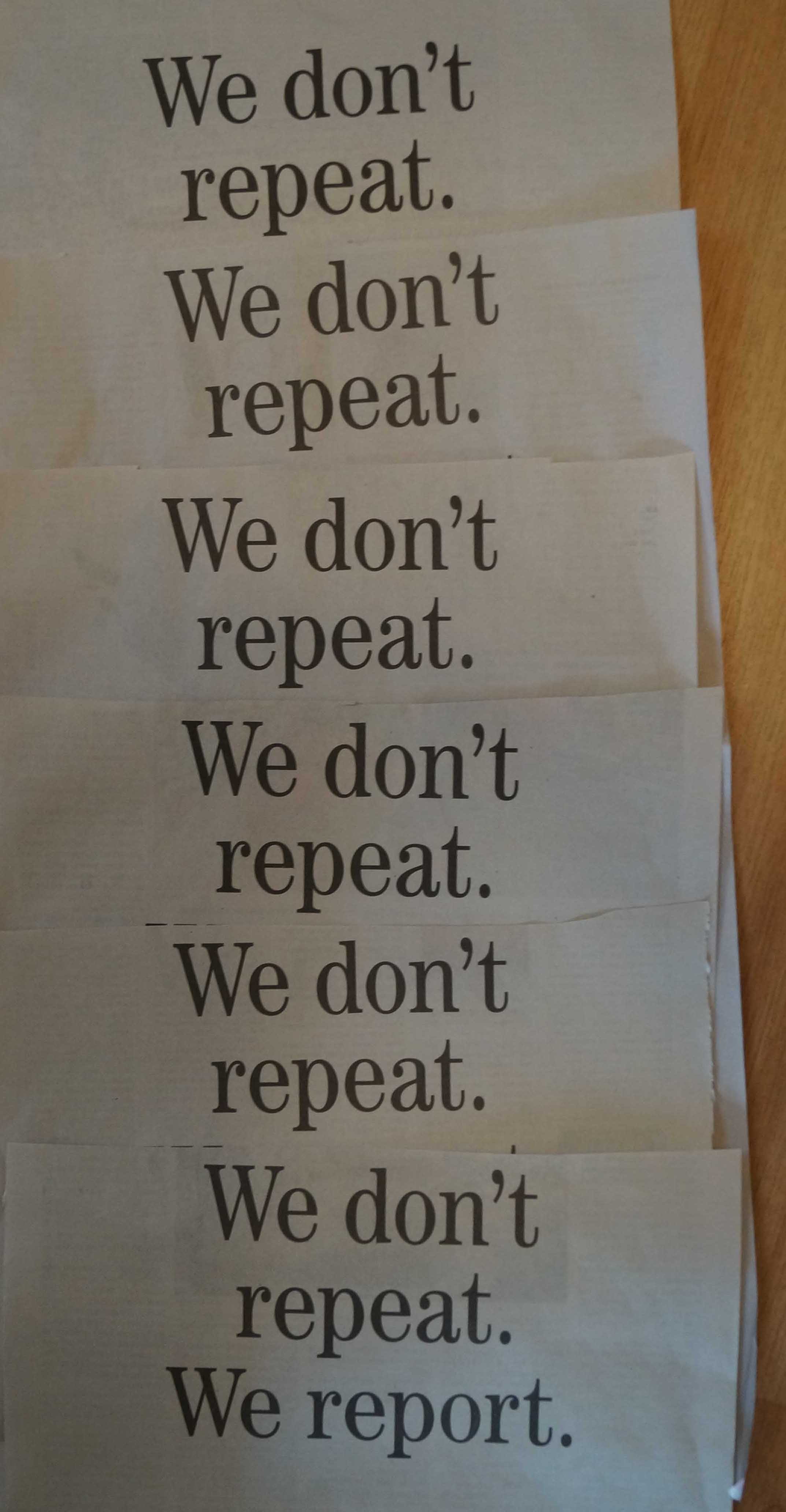

We Don’t Repeat

April 23, 2020 - #

In an uncertain, disquieting world, it is reassuring to have moments that are predictable. For me, one such moment comes every morning when the Toronto Star lands on my doorstep. When I pick it up and take it inside, I am comforted by the knowledge that even though almost the entire paper will be full of COVID-19 coverage, every day the Star will manage to find one page to run a self-laudatory full-page ad telling me that

“We don’t repeat... We don’t repeat... We don’t repeat... We don’t repeat... We don’t repeat... We don’t repeat... We don’t repeat...”

Nature Calendar May: Prothonotary Warbler

May 1, 2020 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, May: Prothonotary Warbler, Rondeau, May 2018. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Thinking Clearly in a Time of Crisis

May 12, 2020 - #

A crisis like this pandemic is not a time to stop thinking. It is a time when critical thinking and public discussion are more important than ever.

A small number of officials and politicians are taking decisions with enormous and far-reaching implications for the lives of many people, not just for the duration of this pandemic, but far into the future. The time to have serious discussions about what they are doing, and the direction we are heading in, is now, not some day in the future when it will be difficult, or too late, to change course.

To be clear: I believe that public health officials, the people who are taking a leading role in shaping our response to COVID-19, are doing their best to deal with a very real crisis. I respect their dedication, and I know that it is very difficult to respond to a rapidly changing situation with imperfect information and limited resources. And I certainly have no stomach for the rapidly spreading pandemic of conspiracy theories, let alone the disgusting racist attacks on Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer.

Nevertheless, we need to be asking questions....

Read the full article here.

Nature Calendar June: Marsh Marigolds

June 1, 2020 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, June: Marsh Marigolds, MacGregor Point. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

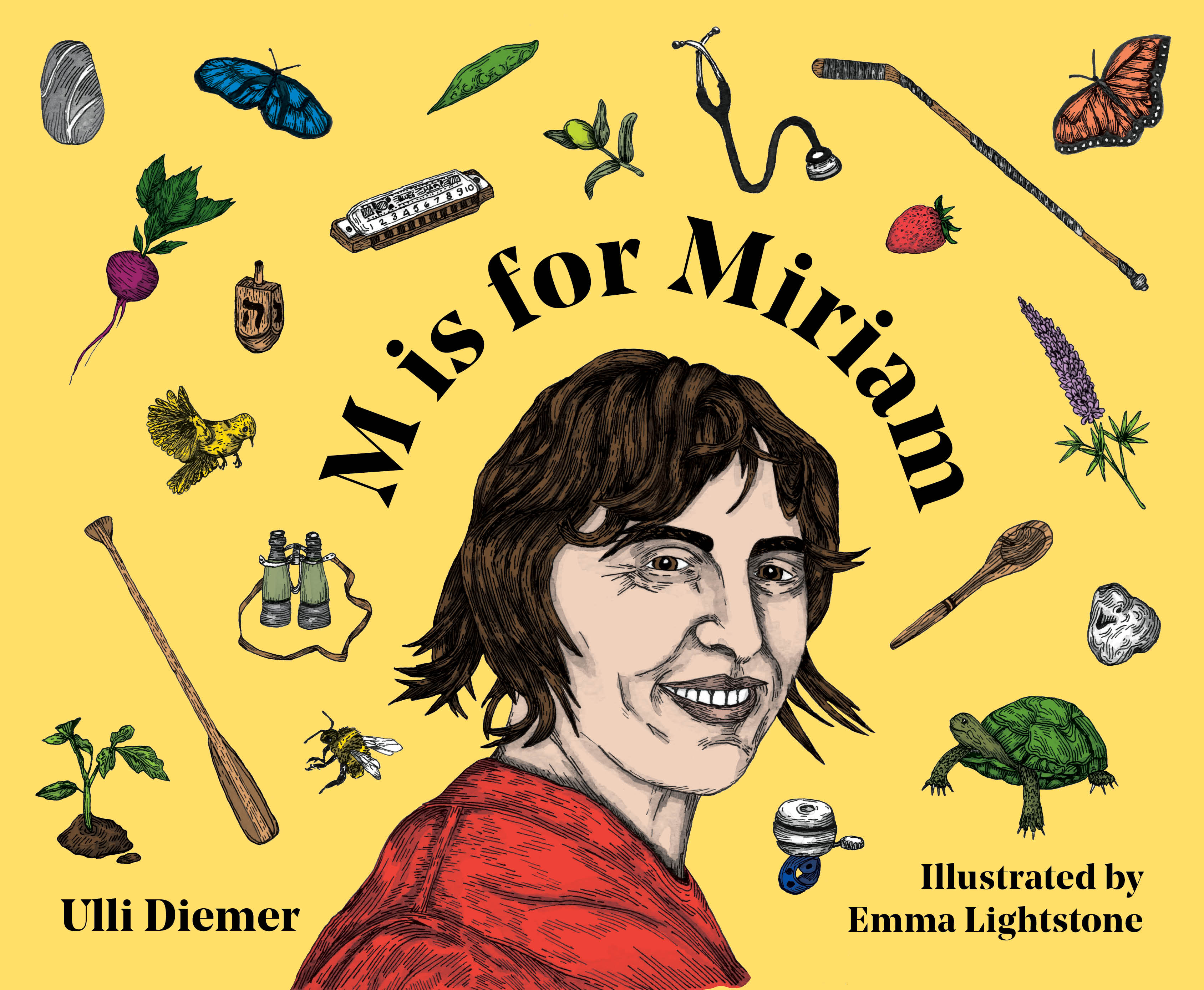

M is for Miriam

June 5, 2020 - #

I’ve written a children’s book about my partner Miriam Garfinkle, who died in September 2018.

It’s an alphabet book, illustrated by Emma Lightstone, with each page devoted to some aspect of Miriam’s life: C is for Community, D is for Doctor, G is for Garden, L is for Laughter, N is for Nature, P is for Piano, Q is for Questions, S is for Solidarity, W is for Waffles....

It’s intended for kids aged roughly three to nine, but adults who knew Miriam seem to like it too. For more information including how to get a copy, see the Contact page.

Strange Sounds Up in the Trees

June 6, 2020 - #

I’m sitting out back reading (Uncle Tungsten, by Oliver Sacks) but I find I’m being distracted by the sounds coming from up in the trees above my head. Usually I have some idea of what I’m hearing from up above – swifts, robins, cardinals, sparrows, squirrels, cicadas later in the summer – but these sounds I can’t place. They’re just weird: a combination of whistles, clacking sounds, chuckling, rattling, in no particular sequence that I can make out, and certainly not musical.

Finally I grab my binoculars and have a look. Two birds, darkish. It’s not so easy to recognize a bird when it’s 30 feet up and you’re directly below it. Not for me, anyway. Hmmn, yellow bills. Aha: starlings. Since they have yellow bills, I presume they are adults, since the young have dark bills. They’re sitting on separate branches, but occasionally one hops onto the branch the other is on. Some kind of mating behaviour? That seems possible, but they don’t seem to be actually doing anything.

I look them up. My Peterson guide says they are “garrulous.” That they are. Another bird book tells me that starlings are “monogamous,” their version of monogamy being that they stick with one partner until they pick a new one. Yeah, OK.

So maybe they’re discussing the pros and cons of raising another brood? Or maybe they just enjoy sitting around making weird noises? I don’t know.

This seems to be the story of my life: I see things, but I don’t really know what’s happening, or why. It wasn’t always like this: when I was 20, I knew everything. Since then, life has been a constant journey of discovery: that is, discovering how much there is to know, and how little I know.

The mosquitoes drive me inside. Back to Oliver Sacks.

Ulli Diemer

Some musings about risk

June 21, 2020 - #

The first time my partner and I arrived in Pukaskwa, a wonderful national park on Lake Superior, planning to spend a week or so camping, we were presented with some disconcerting news. “I just want to inform you,” the person in the registration booth said, “that a woman was attacked by a bear in the park yesterday.”

Not exactly news one wants to hear. I looked at Miriam, she looked at me. We didn’t actually discuss what to do, because we knew each other well enough to assume that we’d have the same reaction, and looking at each other’s expression was enough to confirm that. Off we went to pick a campsite and pitch our tent.

We had encountered enough black bears in the woods over the years that even the news of an attack wasn’t enough to shake our conviction, born of our own and other people’s experience, that bears are usually no trouble as long as you remain alert and, when you encounter one, back off slowly, muttering apologies. Even though we felt sorry for the woman who had been attacked, we suspected, perhaps unjustly, that she must have done something to provoke the bear – and we felt sad when we heard subsequently that the bear had been shot. After all, the park was its home, not ours.

The only time I can recall feeling nervous about a black bear was one time when we encountered a mother with three cubs. We backed off quite expeditiously on that occasion.

Mother with 3 cubs. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

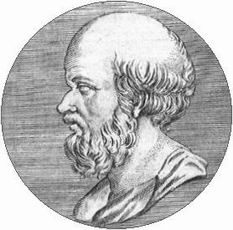

Eratosthenes: Measuring the Earth on the Solstice

June 20, 2020 - #

The Solstice falls at 5:44 EDT on June 20 this year.

It’s a special day, and for nerds like me, it’s also historic because it was on the Solstice in 240 BCE (give or take a couple of years, the record is a bit unclear) that Eratosthenes, a Greek geographer, mathematician, astronomer, poet, and librarian, first calculated the circumference of the earth.

Eratosthenes lived in Alexandria, where he served as the librarian of the great library of Alexandria. He learned from travelling merchants that in the town of Syene, far to the south of Alexandria, on midday on the day of the solstice, the sun shone directly down a deep well, reflecting off the water below, something that happened on no other day of the year.

Eratosthenes knew that the sun would have to be directly overhead for this to happen, and he also knew that this never happened in Alexandria. Using the shadow of a vertical stick, he measured the sun’s angle in Alexandria on day of the Solstice, and found that it was about 7.2 degrees away from being vertical, about one-fiftieth of a circle (360 degrees). He reasoned that if he could measure the distance from Alexandria to Syene, he would then be able to calculate the earth’s circumference.

Traders told him that it took 50 days for their camels to travel from Alexandria to Syene. Eratosthenes knew that travellers riding camels could cover about one hundred stadia (about 11-and-a-half miles) in one day, so he calculated that the distance from Alexandria to Syene was about 5,000 stadia, or about 570 miles. He multiplied this figure by 50, and arrived at an estimate of about 28,500 miles for the earth’s circumference. That’s about 15% off the current measurement of about 24,900 miles; not bad for 240 BCE.

Longing for freedom, and grieving loss: Reflections on watching swifts on a summer evening

June 25, 2020 - #

The chimney swifts lured me outside again this evening. I’d already been out for one walk, but my door was open, and hearing their calls pulled me out in search of them, as it so often does. They’re active in the evenings in my neighbourhood, and going for a walk in the summer pretty much guarantees that you’ll hear them, though seeing them is not always quite as easy.

The tricky thing about seeing swifts is that you hear them, look up to where the sound came from, and they aren’t there. These are birds that can fly 100 km/hour, so if it takes you a half a second to look up, they can already be 100 metres away. They are called swifts for a reason.

Swifts are mysterious birds, enigmatic and paradoxical.

In a sense, they are supremely urban birds, at least during the summer, having adapted themselves to nesting in chimneys a long time ago, though once upon a time they nested in hollow trees. Centuries of logging pretty much eliminated that option, and now they live among us, though as old chimneys get capped or disappear, so do their options for nesting sites. Common swifts and Alpine swifts, species found in Europe, Africa, and the Mediterranean, have been nesting in human-built structures for thousands of years. A swift colony in the Western Wall in Jerusalem has been there for more than 2,000 years: the land has seen enormous changes, but every spring, without fail, the swifts arrive and claim their nests.

Yet unlike other urban birds, swifts have nothing to do with us. They don’t interact with us or hang out in our vicinity in the way that we are used to other birds doing. They don’t perch in trees or on wires, they don’t land on the ground or at a birdbath. They can’t: swifts are so uniquely evolved to a life in the air that they have shed features characteristic of most of the birds we know. Their feet only allow them to cling to vertical surfaces like bricks or trees. That is sufficient for their purposes, because they spend such a small part of their lives down in our terrestrial world.

Nature Calendar July: Painted Turtles

July 1, 2020 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, July: Painted Turtles, Brickworks. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Social Distancing

July 4, 2020 - #

A certain three-year-old very near and dear to my heart (‘B’) came by for a visit today, with his father. Of course, the rules around social distancing need careful thinking about these days, and it’s sometimes difficult for us grown-ups to figure them out, so it’s helpful to have a three-year-old skilled in the use of Socratic questioning to guide you in the right direction.

The visit started out front, me standing on the steps, them down below.

B: Can we go to the backyard?

Dad: OK, we can do that.

[in the backyard]

B: Can I go on the deck?

Dad: No, we have to stay below for social distancing. Ulli will be on the deck.

[90-second interval]

B: Can I sit on the bottom step?

Dad: OK, you can sit on the bottom step.

[60-second interval]

B: Can I sit on this step? (second step)

Dad: OK, you can sit on the second step.

[60-second interval]

B: Can I sit here? (top step/edge of deck)

Dad: OK, you can sit there.

[90-second interval]

B: Can I walk on the deck?

Dad: OK, you can walk on it, on this side.

[60-second interval]

B: Can I put my chair on the deck?

Dad: Oh, OK.

[30-second interval]

B: Can Ulli come sit in the chair beside me?

Dad: Oh, OK.

[Time to achieve goal: five-and-a-half minutes.]

An evening paddle

July 8, 2020 - #

Went canoeing on the Humber River with a friend yesterday evening. We paddled the river and explored the marshes. Saw egrets, great blue heron, grebes, wood ducks, mallards, Canada geese, mute swans, red-winged blackbirds, swallows. Cormorants, gulls, and terns were diving for fish. A highlight was a kingbird nest in a branch above the water, the young with their mouths wide open, the busy parents flying back and forth bringing them insects.

That’s one of the wonderful things about being in a canoe: you can go places you can’t approach in a car or even on foot, moving quietly or staying still in one spot. Life slows down, and you can breathe.

Heat Wave

July 9, 2020 - #

It’s hot. It’s really hot. It has been hot for days in Toronto, and the heat isn’t going away.

I am sitting in my air-conditioned home, reading and writing. Ever since COVID arrived, I have been working from home, so when it is this hot, I mostly stay inside during the day, and only head out for walks early in the morning, and later in the evening. I am very aware of how lucky and privileged I am to have the luxury of living the way I do.

I just picked up Jane Jacobs’ 2004 book Dark Age Ahead (a great book which I highly recommend) and re-read the chapter in which she talks about the 1995 heat wave in Chicago. More than one thousand people in excess of the usual number for that period were admitted to hospitals because of heatstroke and other related effects of the heat. Deaths in Chicago during that week were 739 in excess of a typical summer week. There were so many dead that a fleet of refrigerated trucks belonging to a local meat-packer were used to store the bodies, and even that proved not to be enough. Inevitably, those who died were predominantly poor and elderly.

Butterfly

July 9, 2020 - #

Standing on the front walk with my neighbour, I’m trying to find words, but what is there to say? Her daughter died yesterday. In the face of her grief, I have nothing to offer except my presence and feeble words of sympathy.

It wasn’t so long ago that we were standing on this same spot: I was the one who had lost my beloved, also to breast cancer, and my neighbour was trying to find words of comfort.

My neighbour knows, as do I, that life and death, love and grief, walk hand in hand. She is 92 years old, her husband died more than 20 years ago, and still, every Valentine’s Day, she visits his grave.

Lives end, but life goes on. When she goes back inside, I see a Monarch butterfly flitting around the milkweed plants in the front yard. I hope she is looking for a spot to lay her eggs. A woman is walking by with her young daughter. They stop: the mother points to the butterfly and the milkweed and explains what is happening. The daughter is listening and watching intently.

I smile, despite my sadness. Life goes on.

Ulli Diemer

Monarch Butterfly. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Nature Calendar August: Chipmunk

August 1, 2020 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, August: Chipmunk, Brickworks. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Nature Calendar September: Killarney/Shebahonaning

September 1, 2020 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, September: Killarney/Shebahonaning. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Nature Calendar October: Maples Leaves, Christie Pits

October 1, 2020 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, October: Maples Leaves, Christie Pits. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Nature Calendar November: Carrying Place, Prince Edward Country

November 1, 2020 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, November: Carrying Place, Prince Edward Country. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

November 11

November 11, 2020 - #

November 11. Remembrance Day. The day the Great War – now called the First World War – finally ended. The date has always been a significant one for me, first of all because it is my birthday, but also because the horrors of the war that ended on that day, and the even greater horrors that followed it, had a huge impact on my family, and therefore on me.

Official remembrances are often about forgetting as much as they are about remembering, and “Remembrance Day” is no exception. Why did the fighting end at 11 am on November 11?

Nature Calendar December: Cardinal

December 1, 2020 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, December: Cardinal, High Park. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Nature Calendar 2021

December 2, 2020 - #

Again this year, I created a calendar featuring photos taken by my partner, Miriam Garfinkle, who died on September 15, 2018. Miriam was frequently out in nature, and she’d often have a camera with her. As I did last year, I gathered up some of the photos she took and compiled them in Miriam’s Nature Calendar 2021. I printed about 120 copies for friends and family. The PDF version is available online.

Adding up to Zero

December 6, 2020 - #

As someone who has subscribed to a daily newspaper for all of my adult life, I long ago learned that the real news is to be found in the business section. This is even more true now. The main ‘news’ section (down to a few skimpy pages as newspapers spiral downwards toward bankruptcy) is basically all-COVID, all-the-time, with a few random bits of Trump melodrama thrown in for variety.

It’s from the business section that I just learned that Canada’s biggest meat company is now proclaiming itself both “carbon neutral” and “carbon zero.” I found that difficult to believe, but the newspaper assures me that the company is adding “a jazzy new label to its packaging:” “a seal that declares its products carbon zero,” so it must be true. A corporation wouldn’t put a slogan on its packaging that isn’t true: I take that as an article of faith.

But, sceptic that I am, I still wondered: all those cows and pigs that feed their assembly lines, are they no longer producing the methane gas which we have been told makes a rather significant contribution to greenhouses gases in the atmosphere? And the trucks that haul their products across the country, they’re no longer burning gasoline? And those huge meat processing plants, you know, the ones with all the COVID-19 outbreaks, they’re no longer using fossil fuels?

The people who are preparing for war, and the lies they tell

December 22, 2020 - #

I don’t like Donald Trump. If I was pressed to explain why, I suppose I’d say that part of the reason is that he’s a loathsome racist misogynist lying war criminal. Also, I don’t like people who POST THEIR OPINIONS ALL-CAPS.

I feel I should mention this before explaining why I have a degree of sympathy with Trump supporters who feel that their man is treated unfairly by the mainstream media purveyors of ‘fake news.’ I think they’re quite right. The double standards, hypocrisy, and dishonesty of the media are absolutely breathtaking. That’s true in general, and it’s certainly true in relation to Donald Trump.

A recent example is the alleged hack of Solarwinds, an American software company. Solarwinds’ own report on the alleged hack makes no claim that Russia was responsible, yet within hours the entire mainstream media were pointing the finger at Russia. In a flash, the coverage moved seamlessly from speculating that Russia – not merely Russian hackers, but the Russian state – was behind it, to asserting this as a proven fact, to demanding swift and hard retaliation.

And then President Trump, always the spoiler, chimed in with his own speculation that maybe it was China, not Russia, that was behind it. And anyway, he said, it’s not such a big deal: the U.S. security apparatus is quite capable of handling this kind of thing.

The media were outraged. Shocked! Appalled!

Nature Calendar January: Trumpeter Swans

January 1, 2021 - #

Miriam's Nature Calendar, January: Trumpeter Swans, Leslie Street Spit, Toronto.

Trumpeter swans are impressive, the biggest wild birds in North America. Miriam was always glad when we encountered them because each one we saw was a sign that the effort to bring them back from the edge of extinction is succeeding. Extirpated from most of their range, including Ontario, in the 1800s, Trumpeters are slowly re-establishing themselves. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Nature Calendar February: Point Petre

February 1, 2021 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, February: Point Petre, Prince Edward County.

Each place has its own magic. The lake off Point Petre is usually sunny and inviting in summer. In the winter, the mood is very different. It was a place Miriam appreciated, no matter what side of its changing personality was on display. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Beyond the Walls: The February 14, 2021 edition of Other Voices

Febrary 14, 2021 - #

The February 14 edition of Other Voices, the Connexions newsletter, which I edit, went out by email today. You can see it online here. The introduction to the issue appears below:

Here we are. It’s the middle of February, and we’re still in the midst lockdowns and alarms, missing our normal lives. We could probably all use some sunshine and some cheering up, and surely Other Voices is up to the challenge of providing that?

Absolutely. Sunshine and warmth? You’ll find four items about Gaza and Palestine in this issue. Gaza? Yes, Gaza. Gaza has sunshine, as well as its share of beauty, humour, and giggling children playing amidst the rubble. As Zainab Wael Bahseer writes in Gaza City, an unusual beauty, by carrying on with eyes and ears open, “we teach life.” Her article appears on We are not Numbers, the featured website in this issue, created for Palestinian youth to tell their stories to the world.

In Postcard from a Liberated Gaza Hadeel Assali joins other writers and activists in imagining a post-pandemic, post-occupation Gaza where people drink coffee by the sea and share stories.

Sameer Qumsiyeh, meanwhile, sets out from Palestine, travels to places (not many) which will accept a Palestinian passport, copes with all the additional restrictions of a pandemic, and makes a film, Walled Citizen. His goal in making the film, Qumsiyeh says, was to create "a picture of how things can be if you can transcend walls and barriers."

From Palestine, we continue on to Kashmir, a territory blessed with apple trees, and oppressed by a military regime which, like its counterpart in occupied Palestine, has been destroying those trees by the thousands as part of a strategy of making it impossible for indigenous people to live. Largely cut off from the outside world, Kashmiris nevertheless also continue to live, and to teach life, in the land they are rooted in.

In India itself, people must try to find a way to keep living in the face of poverty and a pandemic made more difficult by a government that is worse than useless. Online classes, offline class divisions tells the stories of students in the Ambujwadi slum in north Mumbai who are trying to manage online learning using borrowed and shared cell phones while continuing to work to help their families survive. Serving customers who come to your vegetable cart while simultaneously continuing to pay attention to what the teacher is saying is part of a normal day for these young people.

John Pilger takes us behind the walls of Belmarsh prison, where Julian Assange continues to be imprisoned even after a court rejected an American extradition request. Watching the trial, Pilger says, was like watching a Stalinist show trial. Although, Pilger points out, at least in a Stalinist show trial, the prisoners were able to stand and face the court directly. Assange was imprisoned behind a thick wall of glass, and could only communicate with his lawyers by crawling on his knees to a slit in the glass to pass out a note, on yellow sticky notepaper, which would then be passed along the length of the courtroom to where his lawyers were sitting. Pilger reminds us that Assange’s “crime” is to have “performed an epic public service: revealing that which we have a right to know: the lies of our governments and the crimes they commit in our name.”

Leonard Peltier remains locked up in the American prison where he has been held for more than 40 years, convicted of a crime he didn’t commit. The International Leonard Peltier Defense Committee continues to work for his release. A film about his life: Warrior: The Life of Leonard Peltier is the featured film in this issue of Other Voices.

The featured book is Viktor Frankl’s “Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything,” written in 1946 not long after he was released from Auschwitz. “As long as we have breath, as long as we are still conscious,” says Frankel, “we are each responsible for answering life’s questions.”

Life asks us to laugh, love, live, and struggle.

Ulli Diemer

The February 14, 2021 edition of Other Voices is online here.

Notwithstanding Clause

Febrary 27, 2021 - #

Rick Salutin, writing in the February 26 Toronto Star, commented on what he calls the Canadian tendency to try to have it both ways: “Canada is a master practitioner of this kind of gesture, particularly when it involves human rights. I call as witness our Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Ambiguity and hypocrisy are built into its core, by way of the notwithstanding clause. Canadians are guaranteed these rights – except if some government, somewhere, for any reason or non, decides we don’t have them after all.” He cited as an example Doug Ford’s unilateral interference in the rules of Toronto’s 2018 municipal election, right in the middle of the election, and Ford’s statement that if anyone tried to stop him, he’d invoke the notwithstanding clause.

I sent Rick an email expressing a different point of view. I said:

I think you are mistaken in thinking that the notwithstanding clause signifies hypocrisy at the core of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. I would argue that, on the contrary, the notwithstanding clause is a vital safeguard.

Even though you say “definitions are overrated,” you seem to assume that “human rights” are objective realities about which there can be no dispute. But “human rights” are hotly disputed, which is why they give rise to legislation, legal challenges, and court rulings.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms laid the basis for decades of judicial activism, with courts asserting the ‘right’ to make sweeping decisions on matters which previously were seen as the purview of Parliament and the provincial legislatures. Courts now routinely overrule laws passed by Parliament.

But courts are not neutral arbiters of objective fact. They are, as commentators from Karl Marx to Harry Glasbeek have explained, class-based institutions presided over by individuals with clear class biases. They often make rulings which are outrageous.

The notwithstanding clause makes it possible for legislatures to overrule the courts. There are times when this is necessary, and a good thing. There are also times, Doug Ford’s outrageous actions around the 2018 municipal election for example, when it can be abused. But given a choice between allowing courts to make unchallengeable rulings, and allowing legislatures to overrule the courts on rare occasions, I think the power to overrule via the notwithstanding clause is preferable. At least we can vote for who forms the government, albeit through an electoral system where government routinely take office with 40% of the vote. We can’t vote to overrule the courts when they make bad decisions, so the notwithstanding clause is at least a meager protection against judicial tyranny.

To bring this down to the nitty-gritty of current events: the courts have recently been faced with legal actions brought by doctors seeking to overturn the Canada Health Act and provincial medicare systems on the grounds that a universal publicly administered single-payer medicare systems infringes on the human rights of wealthy individuals who assert the right to buy their way to the front of the queue, and on the human rights of doctors who want the freedom to make as much money as they can by giving preferential treatment to the well-off. Should the Supreme Court rule against medicare, which it might, given that its membership consists of well-off members of the ruling class who would be quite able to afford the best private health insurance, then I would hope that the government would invoke the notwithstanding clause. And I, and millions of others, would say, thank God for the notwithstanding clause.

Nature Calendar March: Red-winged Blackbird

March 1, 2021 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, March: Red-winged Blackbird, Brickworks, Spring 2013.

Hearing and seeing the first red-winged blackbird of the season is always exciting because it is a sign that spring is going to arrive, even if it hasn't actually arrived yet. The earliest we ever heard a redwing was on February 21 in 2016, in Rattray Marsh. However, it was a warm day in May when Miriam photographed this vigilant male. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Private ownership of long-term care homes means overcrowding and more deaths

March 17, 2021 - #

In an op-ed in the Toronto Star on March 16, Walter Wodchis and Bob Bell offer arguments in defence of privately owned long-term care facilities that are peculiar, to say the least.

The fact that the death rate in privately owned nursing homes has been much higher can’t be blamed on the private ownership of those facilities, they tell us. It’s simply due to the unfortunate fact that privately owned homes cram more people into each room, substantially increasing the risk of infection. These privately owned homes are in urgent need of upgrading and replacement, according to Drs. Wodchis and Bell, and, since the owners have failed to modernize them, despite their substantial profits, they urge that the province pick up the tab for doing so, while leaving the people who have mismanaged these facilities in charge.

The bottom line, which they fail to acknowledge, is that private ownership is associated with overcrowding, failure to invest in modernization, and more deaths. This certainly seems like an argument in favour of ending private ownership of long-term care facilities.

Nature Calendar April: Tree Swallow

April 1, 2021 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, April: Tree Swallow, Colonel Sam Smith Park, Spring 2013.

An extraordinary variety of species have made their homes in Colonel Sam Smith Park, a modest-sized park on Toronto’s waterfront. Over the years, Miriam photographed ducks, grebes, snowy owls, mink, butterflies, and much else. Tree swallows nest there in the spring, dazzling us humans with their speed and beauty. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Situation Normal – April 1, 2021

News from the real world and beyond

April 1, 2021 - #

Death by capitalism # ColdType (Coldtype.net) has been handing out Covid awards. There are many deserving recipients. The Bronze Covid award for February goes to the Italian medical supply company, Intersurgical, which threatened to sue a 3-D printer start-up for producing the company’s ventilator valves during last spring’s Covid emergency in northern Italy. Intersurgical, which charges $11,000 for each valve, had been unable to meet the needs of hospitals overrun with desperately sick patients. So Alessandro Ramaioli and Christian Francassi of Isinnova, a 3-D printer company, reverse engineered the part because Intersurgical refused to release the specifications. The valves they supplied cost $1 apiece. Now Intersurgical is threatening to sue the two Isinnova men for patent violation. The virus had killed more than 97,000 Italians as of December. See Coldtype.net

“Silencing” the unsilent # A March 7 opinion article says it’s “Time to stop silencing women in politics.” The author takes offense to Ontario Premier Doug Ford being bluntly critical of the Leader of the Opposition, the NDP’s Andrea Horwath.

As anyone who follows politics must know, politicians are constantly attacking and putting down opposing politicians. Andrea Horwath, for one, does it on a daily basis.

But if a female politician is criticized by a male politician, then, according to this columnist, the male politician is “silencing” the woman politician. This would appear to be an instance of the broader cultural moment which holds that if anyone disagrees with you, let alone criticizes you, then this creates an “unsafe“ environment and “silences” you. Even though, one can’t help observing, those who proclaim that they have been “silenced” are rarely silent: commonly they are articulate middle-class people who are well able to make themselves heard and make themselves the centre of attention.

Certainly Andrea Horwath, a tough and experienced politician, has not been silenced, not in the least. She is up on her feet pretty much every day, usually in front of a microphone, frequently saying harshly critical things about Premier Ford, who, for his part, is also anything but silent. Politics as usual, in other words.

Facebook offers a few pennies to buy good PR and ward off legislation # Facebook is getting a bit worried about the threat of legislation that could might it to pay for the content created by other media companies (e.g. newspapers and magazines) that is published on the Facebook site. On March 23, 2021, Facebook announced that it will be contributing $8 million to a fund for journalism in Canada. To the newspapers facing extinction, and unemployed journalists and new journalism graduates, this might sound like a lot of money.

For Facebook, not so much. Facebook’s annual reported revenue is $105 billion. To put their $8 million contribution in perspective: a Canadian making the approximate median annual income of $65,000 who gives $5 to charity is contributing a greater percentage of their income than is Facebook.

What I’ve Been Reading

Behind Canadian Barbed Wire, by David J. Carter, and Escape from Canada! by John Melady

Two books about the more than 34,000 German prisoners of war who were held in Canada during the Second World War. My father was one of them. The books describe life in the camps, escape attempts, and how former prisoners remembered their experience. While being a prisoner is no one’s idea of a good time, being held in Canada was for many a blessing in disguise, certainly compared to the fate of the millions who died in the war.

And life in Canada was not that bad, all things considered. In fact, when the war ended, some 6,000 German POWs asked to be allowed to stay in Canada. Under the Geneva Convention, this was not allowed: all POWs had to be returned to their country of origin. Many of them subsequently applied to come back to Canada as immigrants, and several thousand were permitted to do so. Again, my father was among them. Some of the POWs were particularly anxious to return to Canada as quickly as possible because, thanks to relaxed discipline at some of the remote camps, they had ended up with Canadian girlfriends and wives, and in at least one instance, a Canadian-born child.

Where is Here? Canada’s Maps and the Stories They Tell, by Alan Morantz

Morantz describes the ways in which the inhabitants of this land have created and used maps. He situates the creation of maps in the context of their purpose. An Inuit hunter, for example, carried a map in his head, but that map had to be constantly adjusted as snow melt, changing ice conditions, and weather changed the terrain. When Inuit travelled to a new location, the men typically took responsibility for selecting a route to move from one place to another in the safest and most efficient way, but once it was time to set up a new camp, the women took over because they knew how the camp had to be set up, and where to find the best places for finding berries and material for making fires.

Morantz quotes Hooley McLaughlin, who points to the distinction between “teleological maps,” those created with an end in mind, such as road maps and image-based maps, and “dialectical maps,” those made as the journey progresses and which reflect the emotional and physical experience of the map-maker.

Revolutionary Activism in the 1950s and 60s, by Ernie Tate. Volume 1: Canada 1955-1965. Volume 2: Britain 1965-1970. Ernie Tate’s two-volume memoir cover his political activism in the Trotskyist movement from his arrival in Canada from Northern Ireland in 1955, up to 1970. Volume 1 covers his years in Canada, as a member and key organizer for the Socialist Educational League. Volume 2 covers his years in Britain, when his work focused on organizing against the war against Vietnam, as well as on developments in the Fourth International.

How I got vaccinated

April 5, 2021 - #

Having heard horror stories about the difficulties of booking a vaccine appointment online I decided to try the phone number, 1-888-999-6488. I called last Thursday. First off, there was a four-minute recorded announcement about COVID and about what to do if you feel sick (spoiler alert: call Telehealth, or 911 if you are really sick).

Then, within five seconds, a human came on the line, who asked me where I live and how old I am. I aced both questions.

She then offered me an appointment for Monday morning at Toronto Western. She asked me if the location and time were convenient for me. I said yes and yes.

Monday morning, I set off. I had forgotten to bring something to read, which I usually do when I have an appointment, but serendipitously, someone on Palmerston Avenue had left a box of books for people to take. I spotted “A Reading Diary: A Year of Favourite Books” by Alberto Manguel, and took it. It turned out to be a perfect choice.

The wait at the hospital was short. I was led in, asked the usual questions, and got jabbed. Then off to the waiting area to sit for a while in case I had a reaction. My only reactions were to Alberto Manguel’s prose, and those reactions were, as always, positive.

And then home, for coffee and chocolate, which I felt I’d earned.

After I posted this, a reader asked “Why did you rush to take a rush-job vaccine with many unknowns?” I replied:

I have no more concerns about this vaccine (I received Pfizer) that I do about tetanus, hepatitis, and influenza vaccines (not to mention polio, measles, etc.) all of which I have willingly taken. Nothing in life is 100% risk free, but all in all, I think the riskiest thing I did yesterday was crossing several busy streets in downtown Toronto in order to get to the site where I got the vaccine.

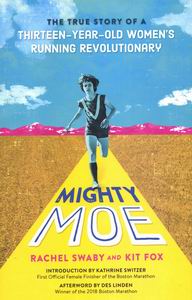

Mighty Moe: book review

April 12, 2021 - #

Mighty Moe tells the story of Maureen Wilton, a youthful long-distance runner from Toronto who set a women’s world record in the marathon in 1967, when she was 13. Wilton didn’t pursue an athletic career: a few years later, she stopped running and turned her life in a different direction: work, marriage, children. As the years passed, her accomplishments faded from memory until John Chipman tracked her down for a 2010 CBC radio documentary “Did My Mom Ever Run?” which gave Maureen, now Maureen Mancuso, another moment in the spotlight.

Authors Rachel Swaby and Kit Fox thought Maureen’s story was a story that should be known more widely. They told it first in a 2017 podcast for Runners World, and then in this book, which broadens the story to include the other young women who were Maureen’s teammates on the North York Track Club, as well as their coach, Sy Mah. The book is primarily aimed at readers aged 10 to 16, but readers of all ages will find it an enjoyable read.

Reading this book transported me back to my own days in the track and field world of North York (then a suburb of Toronto).

Read the rest of the review here

The intelligence of ravens and the foolishness of (some) humans

April 13, 2021 - #

There is something special about ravens. I am always pleased when I encounter them on my wanderings, partly because they make me feel, as Dorothy might say, “Ulli, we’re not in Toronto anymore!”

I am far from alone in feeling that there is something special about them. Ravens feature in the mythology and folklore of many cultures, from North American indigenous peoples to ancient Greek and Celtic legends. They are seen as creators, as destroyers, as tricksters, as harbingers. They can be all those things, because they are complex, adaptable, and highly intelligent.

Knowing my fondness for birds, several people drew my attention to a recent study of the intelligence of ravens, reported in Scientific American, which concluded that “Young Ravens Rival Adult Chimps in a Big Test of General Intelligence.”

I’ve frequently taken pleasure in hearing about and observing how smart ravens and their Corvid relatives are. But this kind of study bothers me.

The first thing that troubles me is the idea that it’s OK to lock up animals in cages and make them perform tricks to test their intelligence or observe their behaviour. Ravens are wild birds meant to live in the wild. If they choose to interact with humans, as they sometimes do, that’s one thing. Caging them against their will so that a few academics can advance their careers by publishing yet another paper, is another thing entirely.

Another thing that bothers me is that studies of this kind continue to propagate the idea that intelligence is a single quantity, a thing that can be measured and quantified. This idea has a long and ignoble history.

Raven, Noris Point, Newfoundland, 2015. Photo by Ulli Diemer.

White-throated Sparrow

April 29, 2021 - #

I’ve been hearing a white throated sparrow out back for the last couple of days. They have been stopping over in the backyard (in downtown Toronto), for a few days every spring for as long as I can remember, certainly more than a decade. It seems a bit mysterious: can they live that long? Do they migrate with their young and tell them: “Remember this place: it's a good place to stop?”

They seem to be arriving earlier. Last year, they were here on May 3. In 2016, it was May 10. I hope that’s OK; they need to be synchronized with their food sources: insects, seeds, berries.

I’ve also learned that some of them have developed a new variation of their song. It was first heard in B.C. in 1999 (I guess cultural innovation often starts on the west coast), and started to be heard in Ontario five years ago. I’m not good enough to be able to tell if this one is singing the old song or the new variation.

I just know that I’m pleased when I hear them: a brief but precious visit.

Update May 2, 2022: The white-throated sparrow arrives once again!

The white-throated sparrow that appears in the backyard every spring is back, singing to announce its arrival. Actually, it’s unlikely to be the same individual, since this is a regular spring occurrence going back quite a few years, and I don’t think they live that long. Perhaps the knowledge of this backyard is passed through the generations? As I wrote last year, “Do they migrate with their young and tell them: ‘Remember this place: it’s a good place to stop?’”

The date varies a bit: Last year, it arrived on April 28. In 2020, it was May 3. In 2016, it was May 10. Whenever it arrives, it makes me happy: a lovely mystery and a precious sound of spring.

Update April 28, 2023: It’s back!

I heard it out back today for the first time this year. Warms my heart.

Deadlines

April 30, 2021

I miss deadlines.

Connexions – the project I work on, which encompasses both a physical archive and an office, as well as the Connexions.org website – shut down in March 2020 because of the pandemic, and clearly we’re still some way from being able to re-open. I wander over to visit the archive space every week or two, just to make sure everything is still OK and run my fingers lovingly over the materials on the shelves, but of course there is no one else there.

I miss the human contact of working with other people, of course – I really miss it! – but I realize that I also miss the deadlines that working with other people imposes. Working with other people – even in an all-volunteer project like Connexions – imposes deadlines. You agree to do something, you set a completion date, and then you work to meet that deadline because you made a commitment. Now that we have to work remotely, we are working much more independently on longer-term projects with few real deadlines.

And that’s a problem for me, because I’ve always depended on deadlines to motivate me. In high school and university, I mostly wrote my essays the night before they were due. That usually worked out pretty well, so I had no reason to change my ways. After that, I moved into journalism, where the typical pattern is that an editor gives you an assignment in the morning, and you have to hand it in, finished, by the end of the afternoon. That also worked well for me.

Nature Calendar May: Swallowtail Butterfly

May 1, 2021 - #

Miriam’s Nature Calendar, May: Tree Swallow, Craigleith Gardens, May 2015.

Miriam rarely had an agenda when she was out in nature. She knew that the best moments, in nature and in life, are those that simply happen. We don’t find them; they find us. So it was on this walk, when we suddenly came upon a group of Swallowtail butterflies feeding on a cluster of flowering shrubs. Photo by Miriam Garfinkle.

Situation Normal – May 1, 2021

News from the real world and beyond

May 1, 2021 - #

Wishful thinking as a climate plan # Canada’s federal government has announced new targets for cutting greenhouse gas emissions. The new target is to reduce emissions by 40% to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030. That’s an increase from the previous target of 30% set by the Harper government. Even so, the targets are inadequate, and all the more so since they don’t count emissions from shipping, air travel, and the military.

What the new plan also doesn’t include is any plausible strategy for achieving these targets. We’ll continue the present approach of trusting that ‘market mechanisms’ coupled with subsidies for ‘innovative technology’ (and pipelines) will somehow get us there.

That’s the approach that has resulted in a 1 per cent drop in emissions since 2005. One per cent in 15 years. If we continue at the current rate, it will take us roughly 675 years to achieve those targets. The new climate plan isn’t a plan: it’s a fantasy.

Greening the energy sector An article in the business section describes what it calls the “greening of the energy sector.” One strategy for doing this, it seems, is that some companies are selling oil assets to other companies which don’t care so much about pretending to be green. So the company that sells off oil assets can position itself as ‘green’ by showing that it has reduced its activities in the oil and gas sector. Of course, the oil and gas is still being extracted and burned, by someone else.

Some people may be fooled by this, but the planet is not fooled.

Paid sick days # After more than a year of refusing the act, Ontario’s Conservative government is finally proposing a wholly inadequate sick leave plan. The Ford government deserves all the criticism it has been getting, but there is another side to the issue: the refusal of businesses to act on this on their own.

I used to own a small business. We provided paid sick days, not because the law required us to do so, but because it was the right thing to do. We also recognized that having workers come to work sick and possibly make other employees sick was not in our interest.

If a small company like ours could act on its own to provide paid sick days, then corporations many times bigger than ours, could do it too. The fact that they don’t shows that they value profits over their workers’ health.

Vatican approves vaccines ... but some Catholics disagree The Vatican has said it is permissible for Catholics to received vaccines that may incorporate, as many of them do, cell lines from fetuses that were aborted decades ago. The Vatican said “It is morally acceptable to receive Covid-19 vaccines that have used cell lines from aborted fetuses in their research and production process” and that “the use of such vaccines does not constitute formal cooperation with the abortion from which the cells used in production of the vaccines derive.” Both Pope Francis and former Pope Benedikt have received the vaccines.

However, some conservative Catholics are objecting. They maintain that anything that derives in some way from the “evil” of abortion, no matter how remote, must be rejected by Catholics of good conscience. One has to ask: how is it possible for these ‘people of good conscience’ to participate in a church with a history that includes the sexual abuse of children and burning people at the stake?

The myth of Indigenous vaccine hesitancy There have been claims that Indigenous people are reluctant to be vaccinated because of the traumatic legacy of residential schools, and the racism that has historically denied them equal access to health care. Those are the proposed explanations, but it turns out there is nothing to explain, because, as reported in the Toronto Star, Indigenous people get vaccinated at basically the same rate as non-Indigenous people. A Health Canada survey found that 97 per cent of reserve residents, and 94 per cent of Inuit, regard it as important to get their children vaccinated. This is a lower rate of 'vaccine hesitancy' than exists in the non-Native population.

Veldon Coburn, an assistant professor at the University of Ottawa’s Institute of Indigenous Research and Studies, observed that children in Indigenous communities get vaccinated routinely. “We get needles all the time,” he said. “It is not a traumatic experience.”

Coburn suggests that there’s a “cultural zeitgeist” that makes some people think Indigenous people are “very delicate” and need others to care for them. “It’s sort of a self-flagellation from certain segments of the populations,” he said. “They sort of invented an injury that didn’t exist, and they want to be the crutch.”