Ulli Diemer — Radical Digressions

Articles Lists

- Selected Articles

- Articles in English

- Articles in French

- Articles in Spanish

- Articles in German

- Articles in Other Languages

- Articles A-Z

- RSS feed

- Subject Index

Selected Topics

- Alternative Media

- Anarchism

- Bullshit

- Capital Punishment

- Censorship

- Chess

- Civil Liberties

- Collective Memory

- Community Organizing

- Consensus Decision-making

- Democratization

- Double Standards

- Drinking Water

- Free Speech

- Guilt

- Health Care

- History

- Identity Politics

- Interviews & Conversations

- Israel/Palestine

- Libertarian Socialism

- Marxism

- Men’s Issues

- Moments

- Monogamy

- Nature

- Neo-Liberalism

- New Democratic Party (NDP)

- Obituaries & Tributes

- Political Humour/Satire

- Public Safety

- Safe Spaces

- Self-Determination

- Socialism

- Spam

- Revolution

- Trotskyism

Blogs & Notes

- Latest Post

- Notebook 11

- Notebook 10

- Notebook 9

- Notebook 8

- Notebook 7

- Notebook 6

- Notebook 5

- Notebook 4

- Notebook 3

- Notebook 2

- Notebook 1

- Scrapbook

Compilations & Resources

- Connexions

- Other Voices newsletter

- Seeds of Fire

- Alternative Media List

- Manifestos & Visions

- Marxism page

- Socialism page

- Organizing Resources

- People’s History, Memory, Archives

- Connexions Quotations page

- Sources

- What I’ve been reading

- What I’ve been watching

Words of Wisdom

- Revolution is necessary not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew.

- – Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels

Seeds of Fire:

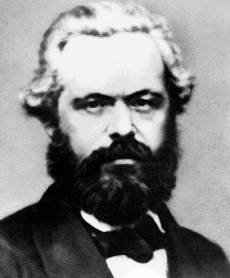

Birth of Karl Marx, May 5, 1818

By Ulli Diemer

Marx breathes dialectics and revolution. For Marx, radicalism means going to the root, and Marx’s radicalism seeks to go to the root of capitalism, to comprehend its essence dialectically, to understand its inherent contradictions – and the seeds of revolution it contains.

The social reality he sees is not fixed and static, but charged with inner tensions and contradictions, which build up until they burst through the constraints of the present order to assume new forms, again with their own tensions, containing the seeds of yet further transformations. In capitalist society, he writes, “All fixed, fast frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.”

Marx comes to socialism, unlike his predecessors, not by drawing up blueprints for imaginary utopias, but through his involvement in the real struggle for democracy.

Here is the heart of his politics: there can be no democracy without socialism, and no socialism without democracy.

He starts to study economics, not because of theoretical preconceptions, but because, as a radical journalist, he is trying to better understand the oppression of the poor peasants whose struggles he is striving to bring to public attention.

Marx never constructs a finished system: on the contrary, he struggles to finish anything he writes because there is always more to learn, always further complexities to study and analyze. He hopes to finish the manuscript that becomes “Capital” in a few months; twenty-four years later, it remains only partially completed, and his friend Friedrich Engels has to complete it after his death.

Marx is always deepening his analysis in response to events: from local struggles of weavers and the rural poor in Germany, to the resistance to British imperialism in India, to the struggle against slavery in the United States, to the Paris Commune, to the long campaign to win the eight-hour day.

He continuously adjusts his theories to the facts, not the facts to his theory. Exasperated by pedantic admirers who proclaim a “Marxist” orthodoxy, he growls “If anything is certain, it is that I myself am not a Marxist.”

His investigations bring him to an understanding of the class nature of society: how economic relations, relations of production, shape a society, including its state forms and ideology. He sees, too, that class struggle is inevitable, and that, further, it is the force that can transform societies.

Marx’s analysis shows that the contradictions of capitalism cannot be resolved: capitalism is a system of continuous crisis, capable of destroying the planet on which it feeds in its endless need to extract more profit, more surplus value, and accumulate more capital. Marx is clear about the danger capitalism poses to the earth: he writes angrily about the destruction it wreaks, and reminds us that we are “not the owners of the globe.” Far ahead of his time, he writes about the metabolic rift between human and nature that capitalism has brought about, a form of alienation which threatens to irreparably damage the ecology of the planet.

Marx’s ecological perspectives, and much of his other analysis, were not published in his lifetime. For many decades, all that even Marxists knew of Marx’s work was restricted to three volumes of his Selected Works, plus the three volumes of Capital. In recent years, work on his unpublished writings has been proceeding: the full collection of Marx and Engels’ collected works is now projected to encompass 125 volumes. A much fuller picture of Marx is emerging. For example, those who think of Marx as Eurocentric would be surprised at how carefully he studied Indigenous societies, and at his conclusion that the most democratic and free society to exist to date was that of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), even though he noted ways in which even it fell short.

Marx’s theory of crisis is not a theory that capitalism will simply collapse one day. He understands clearly that, for all of its contradictions, capitalism will not fall on its own: it needs to be overthrown. He is a revolutionary, not an economic determinist.

Marx believes that there exists a social majority – the working classes, the people who do the work of the society – who are capable of overthrowing capitalism and the capitalist state, and who in doing so can liberate themselves, and all of society. He believes that revolutionaries should engage themselves in the struggles that confront them where they live, but he is clear that finally a revolution that overthrows capitalism, a global system, must be an international revolution.

Marx is clear in his views, but practical in his politics. He throws himself into the work of the First International, which at the beginning is not even explicitly socialist, because he believes it is important to work with others who are engaged in struggle. He never tries to form a political party, and while he usually describes himself as a “communist”, he also at times calls himself a “socialist” or an “anarchist”, without troubling himself much about the terminology.

Running through everything he does is a profound and passionate belief in self-emancipation. He has no time for would-be dictators and saviours who want to bring ‘liberation’ from the outside. Liberation, for Marx, can only be self-liberation: the collective act of individuals working together to emancipate themselves. “Free association” is his watchword, both for the struggle and for the society that we hope to bring into being.

He knows that he won’t live to see that future communist society whose watchword will be “from each according to their ability, to each according to their need” but he devotes his entire life to bringing it about.

This article is also available in German

Related:

Marxism Gateway

Seeds of Fire

Were Marx’s principles only skin-deep?

Keywords:

Dialectics –

Karl Marx –

Marxism –

Marxism Overviews –

Revolution –

Revolutionary Politics –

Self-Emancipation